The other huge budget deficit is at the Fed!

President Trump’s DOGE will be trying to reduce the federal government’s huge budget deficit, but there is yet another big budget deficit in Washington.

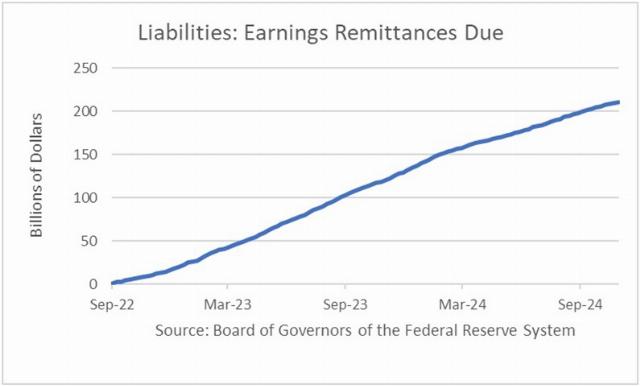

In a November 22 tweet, Heritage Foundation economist E.J. Antoni highlighted the fact that the Federal Reserve now has debt exceeding $210 billion. To illustrate his point, he included a graph, taken from the same Fed website as the one below, which showed that, before Powell, the Fed had no debts, but under Powell, the Fed now owes the government more than $210 billion, and worsening:

How is it possible for the Fed to owe the government so much money? The Fed currently owns $6.64 trillion’s worth of government bonds and other securities. Assuming that those securities pay an average of 4% interest, the Fed is earning about $266 billion in interest each year. Before Powell, the Fed would always give some of its interest earnings back to the government as remittances. No longer.

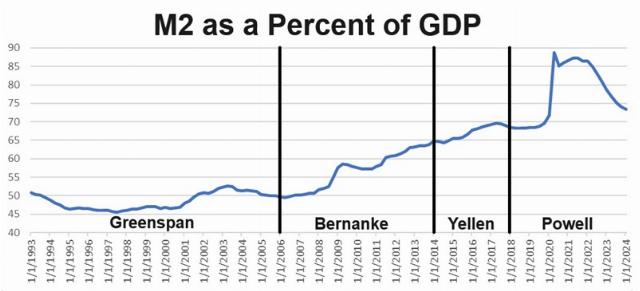

But the blame is not just on Powell. The incompetence at the Fed began in 2010, when Ben Bernanke was Fed chair. Bernanke’s predecessor, Alan Greenspan, had done a good job of keeping the economy on an even keel. He kept money supply fairly close to 50% of GDP throughout his term. Whenever the economy was experiencing excess unemployment, he would increase the money supply, and whenever it was experiencing excess inflation, he would decrease the money supply. Through these adjustments, he was able to prevent severe recessions and also prevent inflationary expectations from ever getting ingrained.

But when the Great Recession hit in 2008, Bernanke greatly increased the money supply (Quantitative Easing), which ended the recession even before the Keynesian stimulus program passed by Congress (TARP) went into effect. He would have gone down in history as a great Federal Reserve chair, but in 2010, instead of bringing the money supply back down toward 50% of GDP, he kept increasing it, as did his incompetent successors Janet Yellen and Jerome Powell, as shown in the following graph of money supply (M2) as a percent of nominal GDP:

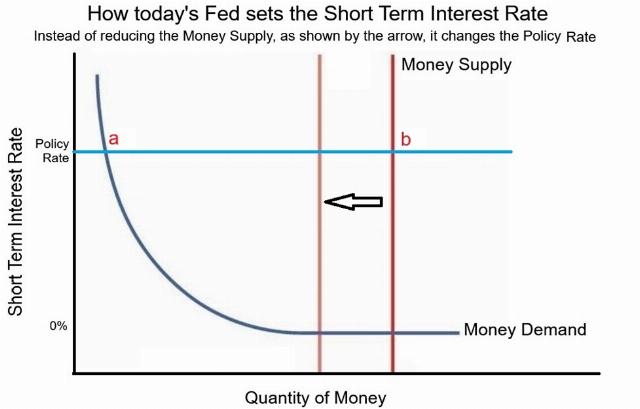

Inflation didn’t shoot back up until 2021 after President Biden restricted US oil production driving worldwide oil prices sky-high. Powell could have fought inflation by bringing the money supply back down to about 50% of GDP (by selling about half of its bond holdings), but instead, he set a price floor, the “Policy Rate” shown in the supply-demand graph below:

The “Policy Rate” consists of several interest rates, all within a tight range. One of these, the Interest on Reserve Balances Rate (currently 4.65%), is paid to member banks, and another, the ON RRP Rate (currently 4.55%), is paid to other short-term lenders, including money market funds and insurance companies. These rates prevent short-term lending at lower rates.

Economists know that price floors can be very expensive for governments to maintain, and this floor is no exception. In order to maintain it, the Fed is paying out oodles of money in interest — the difference between points b and a in the above graph. As a result, despite earning about $266 billion per year in interest, the Fed keeps going deeper and deeper into debt.

Not only that, but price floors didn’t work out very well for Powell. They failed to bring down inflation in a timely fashion, allowing inflationary expectations to become ingrained in the U.S. economy, as indicated by the persistent core inflation rate of 3.3%.

When Powell’s current term ends in May 2026, Trump will have the opportunity to replace him with someone competent who will bring the money supply down to normal levels so that the Fed can fight inflation more effectively and won’t continue to run huge budget deficits.

Howard Richman co-authored the 2014 book Balanced Trade, published by Lexington Books, and the 2008 book Trading Away Our Future, published by Ideal Taxes Association.

Image: Jerome Powell. Credit: Federalreserve via Flickr, public domain.

FOLLOW US ON

Recent Articles

- Public School Teachers: The Stupidest Creatures on the Planet

- The Activist Judges Who Think They Outrank the President

- Dismantling USAID Services in Africa

- There Are EVs And There Are Teslas. They Are Not The Same.

- Trump Didn't Kill the Old World Order -- He Just Pronounced It Dead

- Dems 2025: Stalingrad II or Keystone Kops?

- Go, Canada! Breaking Up Is Not Hard to Do

- Is Australia Set to Become a Security Threat for the United States?

- The Imperial Judiciary Of The United States

- Sanders and AOC: 100 Years of Socialism

Blog Posts

- Rep. Jasmine Crockett mocks Texas's wheelchair-bound governor Abbott as 'Gov. Hot Wheels,' then keeps digging

- The disturbing things that happen when you abandon Biblical principles

- In California, an anguished Dem base urges its politicians to be more crazy

- A new low: Leftist terrorists damage the Tesla of a woman in a wheelchair, leaving her with repair costs

- A Tale of Two Families

- ‘Gruesome’ trans-ing of animals is the key to fine-tuning trans ‘care’

- New report: NYPD officer accused of spying for the Chinese…from the same building as the FBI field office

- Quebec to ban religious symbols in schools?

- Joe Biden can help Republicans

- Low-hanging fruit is not enough

- Trump Makes Coal Great Again

- Israel’s appearance in the JFK files does not connect it to JFK’s death

- Waiting for an investigation of COVID-19 crimes

- Has Women’s History Month served its purpose?

- Democrats and their digging