Congressional dirty dealing is now on full display

The proposed language of the next continuing resolution seems to be back on the drawing board. One of the big questions, though, about the 1,547-page monstrosity that just died in the House is how we can hold accountable the people who created it. Many are saying that bills should identify who’s behind each proposal. In fact, they do. The problem is that this was not a bill. Instead, it was a deliberately opaque runaround using House rules that was intended to hide the actors behind its content.

In civics class, we learned about the legislative process. Here’s how the House describes it:

How Are Laws Made?

Laws begin as ideas. First, a representative sponsors a bill. The bill is then assigned to a committee for study. If released by the committee, the bill is put on a calendar to be voted on, debated or amended. If the bill passes by simple majority (218 of 435), the bill moves to the Senate. In the Senate, the bill is assigned to another committee and, if released, debated and voted on. Again, a simple majority (51 of 100) passes the bill. Finally, a conference committee made of House and Senate members works out any differences between the House and Senate versions of the bill. The resulting bill returns to the House and Senate for final approval. The Government Publishing Office prints the revised bill in a process called enrolling. The President has 10 days to sign or veto the enrolled bill.

It seems straightforward enough. Congress also goes into more tedious detail explaining the process here.

Some of that detail is reassuring. For instance, “One of the most practical safeguards of the American democratic way of life is this legislative process with its emphasis on the protection of the minority, allowing ample opportunity to all sides to be heard and make their views known.” (Emphasis mine.) And “The committees provide the most intensive consideration to a proposed measure as well as the forum where the public is given their opportunity to be heard.”

That didn’t happen here. Bill Ackman’s comment needs to be explored further:

Imagine if all bills were required to be footnoted with references to which Congressman added a provision to a bill. We could then see from whence the pork comes.

— Bill Ackman (@BillAckman) December 19, 2024

The way it has historically been done, there is no cost to being behind a particularly egregious piece of pork.… https://t.co/VyouMo2jm3

Imagine if all bills were required to be footnoted with references to which Congressman added a provision to a bill. We could then see from whence the pork comes.

The way it has historically been done, there is no cost to being behind a particularly egregious piece of pork. With this change, there would be a cost to even proposing government waste.

In fact, bills do have these footnotes. If one accesses the database for legislation at Congress.gov, there is a way to see all amendments proposed to a bill, their authors, and their dispositions. Again, sometimes tedious but clear.

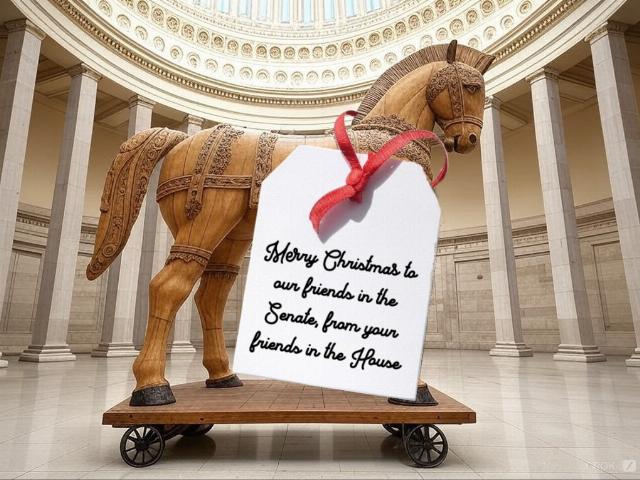

Image made using Grok AI.

However, what we have all been discussing and reviewing was not a bill. It was a 1,547-page-long House document, which is a different beast entirely. It would never have become a bill and gone through the standard House and Senate committee processes. Congressmen and women, our elected representatives, were never going to be allowed to debate the details. Our voices were never going to be heard.

How do I know? Occasionally, I’ve written about legislative processes here at American Thinker. As I’ve prepared these essays, I’ve read and researched thousands of pieces of legislation. Based on what I learned, I can tell you what was to have happened:

After the document emerges from committee, it goes to the House. Once there, there is no debate because it’s not a bill. Instead, there’s a straight up-or-down vote. If there are enough “ayes,” the document goes to the Senate.

In the Senate, there are multiple bills, often short and inconsequential, that have already passed both the House and the Senate and need only to get the president’s signature to become law. One of these passed bills is transformed into a Trojan horse for the House document. The mechanism is to attach the document to the bill as an amendment.

At this point, we see a repeat of what occurred in the House with the original document: A Senate committee approves the bill as “amended” and brings it to the floor for a straight up-or-down vote. There are no hearings or debates. Instead, if there are enough “ayes,” the amendment-via-substitution process means the 1,547-page attachment is labeled as the bill’s “for other purposes” amendment. Then, the original bill, as amended, goes to the president for his signature.

(You can see how this works by going here and reading how a six-page bill about fire grants and safety overhauled America’s entire non-military nuclear policy without any debate or even public awareness.)

This process is deliberately opaque. Where is this method for pulling the wool over the electorate’s eyes spelled out? In the 1,533 pages of the 117th Congress’ Rules for the House of Representatives, as adopted and amended by the 118th Congress’ 52-page-long HRes-5. I wonder how many Members have even read these, or do they just go along unthinkingly?

This is how you hide a bill’s origins. This is how the sausage gets stuffed with no one the wiser about who proposed which bits of text that are finally included or left out. This is how all the Members, collectively and individually, avoid accountability for their actions. This is the nefarious, murky, underhanded, devious, and sneaky process by which favors are traded back and forth, the naïve are excluded entirely, constituents are kept in the dark, and Members’ personal agendas and grievances are addressed.

It’s time to cut this out and give us the transparency we were promised.

Vivek Ramaswami proposed what most of We the People would like to see happen:

Yes, it *is* possible to enact a simple 1-page Continuing Resolution, instead of 1,500+ page omnibus pork-fest. Here it is. pic.twitter.com/2NBcDXtL03

— Vivek Ramaswamy (@VivekGRamaswamy) December 18, 2024

It should. Today.

Anony Mee is the nom de blog of a retired public servant. She X-tweets here.

FOLLOW US ON

Recent Articles

- Public School Teachers: The Stupidest Creatures on the Planet

- The Activist Judges Who Think They Outrank the President

- Dismantling USAID Services in Africa

- There Are EVs And There Are Teslas. They Are Not The Same.

- Trump Didn't Kill the Old World Order -- He Just Pronounced It Dead

- Dems 2025: Stalingrad II or Keystone Kops?

- Go, Canada! Breaking Up Is Not Hard to Do

- Is Australia Set to Become a Security Threat for the United States?

- The Imperial Judiciary Of The United States

- Sanders and AOC: 100 Years of Socialism

Blog Posts

- Rep. Jasmine Crockett mocks Texas's wheelchair-bound governor Abbott as 'Gov. Hot Wheels,' then keeps digging

- The disturbing things that happen when you abandon Biblical principles

- In California, an anguished Dem base urges its politicians to be more crazy

- A new low: Leftist terrorists damage the Tesla of a woman in a wheelchair, leaving her with repair costs

- A Tale of Two Families

- ‘Gruesome’ trans-ing of animals is the key to fine-tuning trans ‘care’

- New report: NYPD officer accused of spying for the Chinese…from the same building as the FBI field office

- Quebec to ban religious symbols in schools?

- Joe Biden can help Republicans

- Low-hanging fruit is not enough

- Trump Makes Coal Great Again

- Israel’s appearance in the JFK files does not connect it to JFK’s death

- Waiting for an investigation of COVID-19 crimes

- Has Women’s History Month served its purpose?

- Democrats and their digging