Celebrating America’s history in Charleston, South Carolina

I grew up in a Europe-oriented household, which wasn’t a surprise given that my parents were both Europeans. My childhood trips never got further than the Western U.S. because we couldn’t afford anything other than long car drives, camping, and Motel 6. However, when I was older, with more money for travel, the people in my life still wanted Europe, always Europe, the center of Western civilization.

Now, though, I don’t want my money to go to Europe, which does not love me, whether as a Jew or an American. Thankfully, though, America has some of its own rich, Western civilization-style history, and I literally got to taste some of it yesterday.

I currently live just outside of Charleston, South Carolina, one of the most historic cities in America if you like 18th- and 19th-century history.

Charleston entered Western civilization in 1670 when Charles II granted the province of Carolina to eight of his most loyal supporters, who aided his restoration to the throne. Immediately after, Englishmen already living in Bermuda and Barbados came as settlers, bringing with them the slavery tradition from those islands.

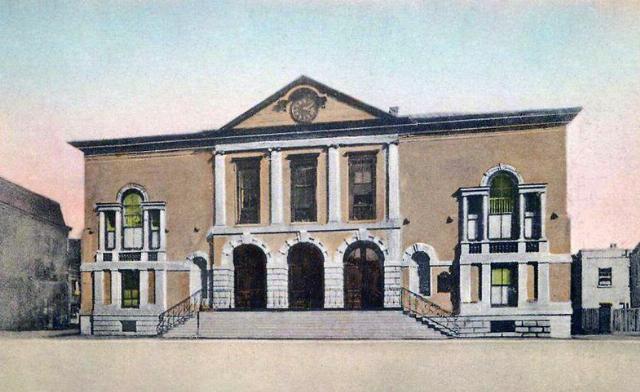

The Exchange Building, which was home to pirates and (imprisoned) patriots, and which played a role in Charleston’s civilized and effective Tea Party. Public domain image.

Although their plantations spread far and wide, it was Charleston, which sits on a huge natural harbor that benefits from the trade winds, that became the main city. The city’s model constitution came from none other than John Locke.

While Locke’s vision was never formally ratified, it did influence the growing city. Although Charleston was a slavery hub (40% of all slaves that came into America before the trade was shut down came through Charleston), the city was remarkable for its religious tolerance.

Charleston became known as “the Holy City” because it allowed all Protestants and Jews to practice their faiths openly, as long as they paid taxes to the official Church of England, a level of religious freedom unknown in most of the world at the time. Only Catholicism was banned, which was partially a political decision, given that England was in hot and cold wars with Catholic France and Spain for Charleston’s first century.

Of course, Charleston wasn’t only shipping slaves. Before the Revolution, it was the world’s major rice- and indigo-producing region, and after the Revolution, it added cotton to the list.

When it came to indigo production, the impetus for that was Eliza Lucas Pinckney, who began running her father’s plantations single-handedly when she was only 16. It was she who spent years figuring out how to get the beautiful, valuable blue dye out of the indigo plant, a secret the French had long guarded. (It turns out to need fermentation.)

In the true spirit of free trade, once Pinckney figured out the technique, she didn’t try to keep it a secret. She realized that she would benefit only if there were a robust indigo trade out of the Carolina colony. Therefore, she made her secret available to all comers, helping to spark a huge economic boom.

By the time of the American Revolution, Charleston was the richest city in the thirteen colonies, and it maintained its economic preeminence all the way through the Civil War. This wealth is evident in the Colonial and 19th-century architecture that peppers historic downtown Charleston and in the surviving plantations in the region.

Many remember Charleston only as the place where the Civil War began when cadets at the Citadel fired upon Fort Sumter. However, Charleston and South Carolina as a whole played a much richer role in American history.

In 1739, Elizabeth Ann Timothy was the first female publisher and franchise holder in America after she took over the South Carolina Gazette following her husband’s death. The franchise she held was part of Benjamin Franklin’s publishing business.

The first slave revolt in the colonies (an unsuccessful one) was 1740’s Stono Rebellion, in what’s now South Carolina.

The College of Charleston, founded in 1770 and still a thriving institution, was the first municipal college in America.

On June 28, 1776, before the Declaration of Independence was signed, Charlestonians scored the first major victory in the War of Independence when they defeated the British Navy at the Battle of Sullivan’s Island.

Four Charleston residents were signatories to the Declaration of Independence.

More Revolutionary battles were fought in the Carolinas than anyplace else in the thirteen colonies. It’s only because Harvard and Yale scholars wrote the histories that we don’t hear about them.

The first successful submarine attack was launched from Charleston in 1864. You can visit the Hunley, which was recovered in the 1990s from the bottom of Charleston harbor.

After the Civil War, Joseph Hayne Rainey, the first black legislator in the House of Representatives (Republican, of course), had been a slave in South Carolina, and he continued to live in Charleston after the war while serving in Congress.

The poinsettia, that familiar Christmas flower, owes its presence in America and the name by which we know it to Joel Roberts Poinsett, a Charleston native, who was America’s first ambassador to Mexico.

The dance the Charleston originated in and was named after the city.

In 1931, Charleston established the nation’s first official “historic district.” A new zoning ordinance meant that people could no longer tear down the city’s historic structures. Because of this, Charleston has more historic buildings than any other city in America.

So, if you like history, Charleston is the place. Boston and Philadelphia, because of the academic heritage that they’ve rapidly been despoiling, long claimed the mantle of America’s historical cities, but Charleston really is the place to be.

And if you have the chance, I recommend that you do what we did last night and attend a meal at the Historic Table. (The website still has the old name, “Historic Charleston Supper Club.”) Mike Hebb is both a historian and a chef, and he’s combined these two passions into something wonderful: Historically accurate meals held in the historic Fireproof Building, which is the South Carolina Historical Society’s museum.

In addition to a fine dining feast using historically accurate recipes (or, as they were known in the past, “receipts”) from the Charleston area, Mike offers wonderful history lessons about the food and Charleston itself. He’s a font of accurate, apolitical knowledge and is a charming, entertaining speaker. He’s so accessible that if you have children around 12 or over and they’re intellectually curious, they’ll enjoy the experience, too.

So, next time you’re contemplating a vacation, don’t spend your money on a continent that disrespects you and everything you stand for (and, if you’re Jewish, that hates you). Instead, come to Charleston, where you will be dazzled by the city’s beauty and learn amazing things about America’s history.

FOLLOW US ON

Recent Articles

- Can Trump Really Abolish the Department of Education?

- Carney’s Snap Election -- And Trump Saw It Coming

- We Can Cure Democracy, But Can We Cure Stupid?

- George Clooney: Master of Cringe

- Malicious Imbeciles

- Face the Nonsense, Again: Margaret Brennan’s ‘You Should Watch the News’ Moment

- Public School Teachers: The Stupidest Creatures on the Planet

- The Activist Judges Who Think They Outrank the President

- Dismantling USAID Services in Africa

- There Are EVs And There Are Teslas. They Are Not The Same.

Blog Posts

- How Mississippi eliminated the income tax

- The ‘agua’ battle on the border

- Rep. Jasmine Crockett mocks Texas's wheelchair-bound governor Abbott as 'Gov. Hot Wheels,' then keeps digging

- The disturbing things that happen when you abandon Biblical principles

- In California, an anguished Dem base urges its politicians to be more crazy

- A new low: Leftist terrorists damage the Tesla of a woman in a wheelchair, leaving her with repair costs

- A Tale of Two Families

- ‘Gruesome’ trans-ing of animals is the key to fine-tuning trans ‘care’

- New report: NYPD officer accused of spying for the Chinese…from the same building as the FBI field office

- Quebec to ban religious symbols in schools?

- Joe Biden can help Republicans

- Low-hanging fruit is not enough

- Trump Makes Coal Great Again

- Israel’s appearance in the JFK files does not connect it to JFK’s death

- Waiting for an investigation of COVID-19 crimes