Revolvers: is leaving an empty chamber necessary?

During my first civilian police job, revolvers were the only authorized handguns, not only for local law enforcement, but state and federal agencies as well. It was the late 1970s, and while a few semiautos were available such as the Model 1911, the Browning Hi-Power and Smith & Wesson’s Model 39, and later the higher capacity Model 59, all were looked upon by police executives as unproven, unreliable and dangerous. They particularly didn’t like the cocked and locked hammers on the 1911 and Hi-Power. The Model 39 and 59 were S&W’s attempt to corner the law enforcement semiauto market with double action semiautos, which didn’t require cocked and locked hammers.

S&W knew better, but they surely thought they could convince skeptical top cops their mechanisms were just like double action revolvers. They weren’t and aren’t. The first round requires a long, heavy trigger pull, like that of double action revolvers, but because the cycling slide cocks the hammer for each subsequent shot, producing a lighter, shorter single action trigger pull, first and second shots virtually always hit the target in very different places. One could train around this, but not without a great deal of time, effort and ammo, and under pressure, one could never be certain the lesson would stick.

The late Col. Jeff Cooper called double action semiauto mechanisms “an ingenious solution for a nonexistent problem.”

Single action semiautos didn’t have the problem. Their trigger pulls were far shorter and lighter, but those cocked hammers were scary, and most had reliability issues requiring the ministrations of skilled gunsmiths, who were expensive, few and far between. So, everyone carried revolvers, and while I carried semiautos off duty, and advocated for their use, it wasn’t until the 90s that my agency transferred to Glocks. All those years I made do with Colt Pythons, Ruger Security Sixes and finally, a S&W 686.

These days, semiauto and ammo technology have greatly changed, and most semiautos are reliable, safe and accurate right out of the box, but of course, basic safety rules must always be followed.

Graphic: S&W Model 36 Classic. Smith & Wesson.

One of the habits of those days persists today, despite being unnecessary: leaving the chamber of a revolver under the hammer empty. Back in the 70s, the state Parole agency issued S&W revolvers with 2” barrels, tiny grips, and 5-shot cylinders. The head of firearms for that agency, who was old school, as in old enough be actively remember the old West, demanded all agents carry their revolvers with an empty chamber under the hammer, leaving them with only four rounds. As hard as such handguns were to shoot accurately, that was a serious handicap. Why would he do that?

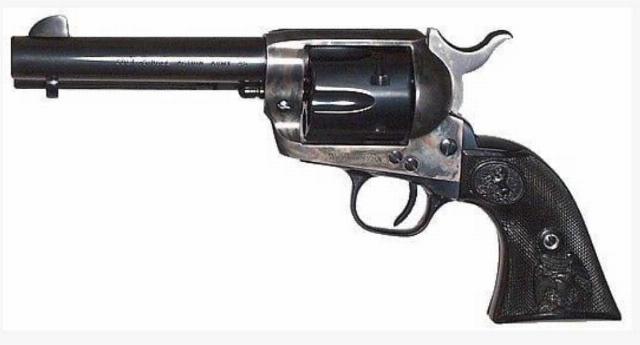

Graphic: Contemporary Colt Single Action Army. Colt.

There is a basis in fact, though I doubt many suggesting that supposed safety measure today know its origin. In the late 1800s, revolvers like the ubiquitous Colt had no safety mechanisms. I’m not referring to external safety levers—revolvers don’t have those—but internal mechanisms like transfer bars, hammer blocks or drop safeties that prevent the weapon from firing unless the trigger is pulled. Firing pins were commonly directly attached to hammers, and a blow on the hammer, from dropping the weapon, or whacking it against something sufficiently hard, could fire a cartridge, thus the only way to carry such revolvers safely was to leave the chamber under the hammer empty, making six-shooters five-shooters. Such revolvers also had “half-cock” notches, allowing the hammer to be partially cocked, which allowed a degree of safety and aided reloading, but they were all too prone to failure and accidental discharge.

By the 70s, virtually every revolver design, even replicas of the Colt Single Action Army, had internal safety mechanisms—empty chambers were no longer necessary--but for old-timers brought up on the practice and many unaware of the nature of modern revolvers, the practice has persisted. Still, one must always be aware of the presence of, or lack of, such safety features in any revolver they own or shoot.

One other revolver fact many seem not to understand is the cartridge in the chamber at rest under the hammer will not be the first round fired. Cocking the hammer manually, or pulling a double action, or double action only, trigger mechanically revolves the cylinder to the next chamber, aligning it precisely with the barrel and firing when the hammer drops, hitting the spring-loaded firing pin and driving it into the primer. That process also removes the transfer bar, allowing the hammer to strike the firing pin. When the trigger cycles fully forward, the transfer bar returns to its safe position.

Be certain of the mechanism of your revolver, but virtually every modern revolver may be safely carried with a fully loaded cylinder.

Mike McDaniel is a USAF veteran, classically trained musician, Japanese and European fencer, life-long athlete, firearm instructor, retired police officer and high school and college English teacher. He is a published author and blogger. His home blog is Stately McDaniel Manor.