Birthright Citizenship: The 14th Amendment Does Not Apply to Illegal Aliens

America is about to go to war over whether the government has the power to deport entire families of illegal aliens. That question involves “birthright citizenship”—that is, whether a child born in the U.S. to illegal alien parents is automatically a U.S. citizen and, thus, an “anchor baby?”

The answer, by any fair reading of the Constitution and history, is “No.”

Our nation must have complete control of our borders. No illegal alien should be able to circumvent the laws of our nation. English common law, the basis for U.S. law, did not allow such people, the children of “hostile occupiers,” to become citizens by virtue of birth. Moreover, the 14th Amendment, which was passed to cure the ill of slavery, establishes a two-part test for citizenship that seemingly codifies English common law and is clearly meant to apply to those who came here against their will and their descendants, not to criminal invaders.

The anchor baby problem is significant. Donald Trump recently said that the Biden administration has “abolished what remained of America’s borders and turned the United States into a dumping ground for illegal aliens from all over the world.” A lowball guess is that Biden’s lawless conduct allowed in at eight least million illegal aliens, although the number could easily be twice that. This influx is causing havoc throughout the U.S.—and even gave rise to a bit of dark musical humor from The Kiffness:

Trump has promised mass deportations—something Americans support—and Tom Homan will be the man accomplishing it. Homan has gone on the record stating the he will deport entire families:

60 minutes: Is there a way to carry out mass deportation without separating families?

— Tim Young (@TimRunsHisMouth) November 6, 2024

Tom Homan: "Of course there is. Families can be deported together."

Put Tom Homan in charge of ICE! pic.twitter.com/fcS48fKu41

Democrats, however, will immediately challenge that plan in the federal court (aided by the fact that Americans are squeamish about separating families). The argument will be based on the legal theory that you can’t deport families when they include an American citizen. The question revolves around “birthright citizenship”: Does a child born of alien parents, especially those here illegally, automatically becomes an American citizen if that child is born inside America’s borders?

A history of birthright citizenship

English Common Law

Because the U.S. was formed on the Anglo legal tradition, the Supreme Court regularly holds that British law before 1776 is the basis of and starting point for American law. That means turning to pre-1776 English citizenship law.

In 1608, the English Exchequer decided Calvin’s Case, which asked whether a Scotsman had the legal right to own land in England. The case’s facts are irrelevant today, but the legal holding is not. As later summarized by Lord Chief Justice Cockburn, two factors can block a child born on English soil from being an English citizen—the children of ambassadors and the children of foreign invaders during a hostile takeover of British territory:

‘By the common law of England, every person born within the dominions of the crown, no matter whether of English or of foreign parents, and, in the latter case, whether the parents were settled, or merely temporarily sojourning, in the country, was an English subject, save only the children of foreign ambassadors (who were excepted because their fathers carried their own nationality with them), or a child born to a foreigner during the hostile occupation of any part of the territories of England. (Emphasis added.)

The emphasized clause aptly describes the children of illegal aliens who unlawfully invade U.S. lands.

Slavery and Citizenship

Slavery muddled the clarity of U.S. citizenship law, coming to a head in 1857 with the Supreme Court’s Dred Scott decision.

Scott was a slave who had sued for his freedom in lower courts. By the time the case reached the Supreme Court, the sole question was, “Can a negro, whose ancestors were imported into this country, and sold as slaves, become a...citizen?”

The Court ruled that Africans and their descendants could not become citizens under federal law because of the interplay between state and federal law and because the federal government lacked the power to outlaw slavery in both the states and the territories. As Prof. Sean Wilentz deftly dissects in his exceptional book, No Property in Man, both holdings boldly misread the Founders’ original intention when drafting the Constitution.

Not long after the Dred Scott decision, the Civil War began. In 1865, when the Confederacy was vanquished, Congress ratified the “Reconstruction Amendments.” The 13th Amendment abolished slavery, the 14th Amendment gave former slaves and freemen equal legal rights, and the 15th Amendment gave former slaves and black freemen the right to vote.

To cure the citizenship question that the Dred Scott case created for former slaves and black freemen, the 14th Amendment created a two-part citizenship test:

All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside. (Emphasis added.)

Unfortunately, little of the debate and legislative history regarding the drafting of this clause was recorded. Additionally, while this formulation seems to restate the law of Calvin’s Case, it is not definitive. What is clear is that mere birth inside of our borders is insufficient to impart citizenship.

Birthright Citizenship and the 14th Amendment

In 1898, the Supreme Court addressed the 14th Amendment’s citizenship clause in United States v. Wong Kim Ark. Wong Kim Ark’s parents were Chinese citizens doing business in America. The government gave them permission to reside lawfully and permanently in the U.S.

Because Wong Kim Ark’s parents were legally domiciled in America, the Supreme Court held that their child was entitled to American citizenship when he was born. That holding is consistent with Calvin’s Case and does not create a precedent for citizenship by illegal aliens exercising a veto over American laws.

The only other case of note happened 90 years later. In 1985’s INS v. Rios-Pineda, Supreme Court Justice Byron White wrote in his recitation of facts that “Deportation proceedings were then instituted against respondents, who by that time had a child, who, being born in the United States, was a United States citizen.” That bare assertion can be safely ignored. This was mere dicta and did not establish new constitutional law. The child’s citizenship was not at issue in the case, and was not argued before the Court.

Summary

The 14th Amendment must be interpreted in light of its time and place. It’s ludicrous to believe that the same Congress that adopted the 14th Amendment to benefit former slaves—people forcibly brought to America and their descendants—meant to change fundamentally the ancient English principle that children born to hostile invaders on English soil (or, in our case, American soil) cannot become citizens.

This interpretation would also run directly counter to the maxim that “it is the inherent right of every independent nation to determine for itself, and according to its own constitution and laws, what classes of persons shall be entitled to its citizenship.” When progressives’ screams about birthright citizenship for illegal aliens’ children reach a fever pitch in the coming weeks and months, know that they are lying to you.

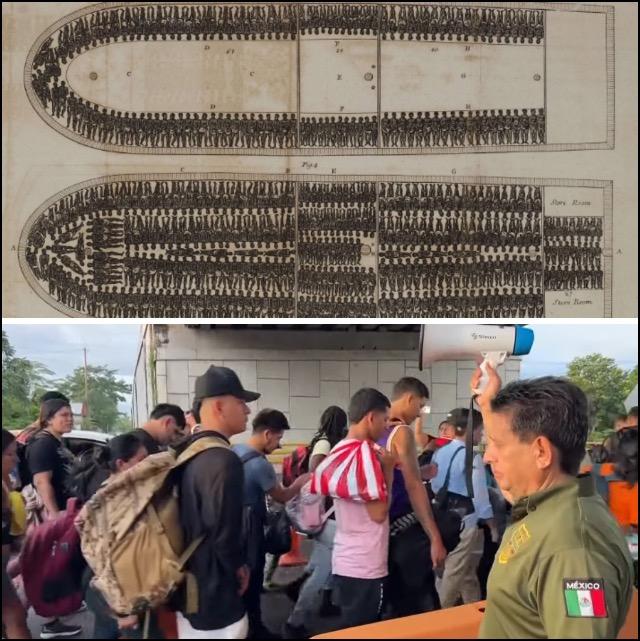

Showing an 1808 drawing of how Africans were transported across the Atlantic and a YouTube screen grab of Latin American men (and a few women) voluntarily invading America. They are not the same.