Thomas Jefferson’s Middle East Policy

Once, American liberals were foreign policy hawks. Indeed, the “Patron Saint” of today’s Democrats, Thomas Jefferson, would not recognize their support for the United States’ religiously avowed enemies, e.g., Hamas and Fatah (Palestinian Authority). In his generation, he was the No.1 national hawk for war in the Middle East.

In May 1784, the Continental Congress signed the Treaty of Paris, the last legal formality in the American Revolution. That same day, it ordered Jefferson to Paris to work with John Adams and Benjamin Franklin as trade commissioners to open up Europe’s closed mercantile system to American commerce. Every state was swamped by Revolutionary War debt, and the remedy was to increase exporting American commodities to England and Europe. Jefferson, however, recognized a threat that could strangle America in its infancy.

With independence from Great Britain, America’s merchant marine no longer enjoyed the protection of the Royal Navy, the greatest in the world—and had sold all of its armed vessels after the Revolution. Without warships, U.S. merchant ships on the high seas would be easy prey for pirates.

Ironically, when Jefferson sailed for France, he was reading Cervantes’s Don Quixote. The so-called “Slave Chapters” are based on the author’s five years as a slave in the port of Algiers, along with hundreds of other Christians kidnapped and enslaved until ransomed.

For 1,000 years, North African Muslims had been hijacking ships and kidnapping and enslaving Christian sailors and passengers for a thousand years, a constant population of Christians slaving on the Barbary Shore (so-called because Christians saw the locals as barbarians).

Once in Paris, Jefferson, thanks to Don Quixote, likely wasn’t too surprised to learn that, in October, corsairs from Morocco had captured the Betsey, an American merchant ship out of Philadelphia with a crew of ten and one passenger. He couldn’t know, though, that, for the next five years, his principal diplomatic efforts would be repeatedly trying and failing to liberate Americans held hostage in the Middle East.

Jefferson studied North Africa’s geography and discovered that the people on France’s fertile Mediterranean coast successfully farmed the land, North Africa’s coast was also potentially fertile. However, its inhabitants preferred kidnapping and enslaving infidels as a livelihood. He questioned fellow diplomats in the city on how their countries handled the problem. Jefferson also bought himself an English translation of the Koran.

He realized that the term “pirates” was inaccurate. These sea-going hijackers from Morocco, Algiers, Tunis, and Tripoli were not venal, free-booting criminals who, when ashore, swigged rum in taverns and pawed at wenches.

Rather than the black and white Skull & Bones flag, their ships flew three flags vertically arranged: lowest was the pennant of the pasha ruling the ship’s home port; in the middle was the ensign of the pasha’s overlord, the Ottoman Sultan in Constantinople; and above all flapped the green flag of Islam. These unusual “pirates” also prayed three times daily to Mecca and were teetotalers.

In 1785, the “Mussulmen” attacked two more American merchant ships, the Maria out of Boston and the Dolphin out of Philadelphia, kidnapping twenty more Americans into slavery.

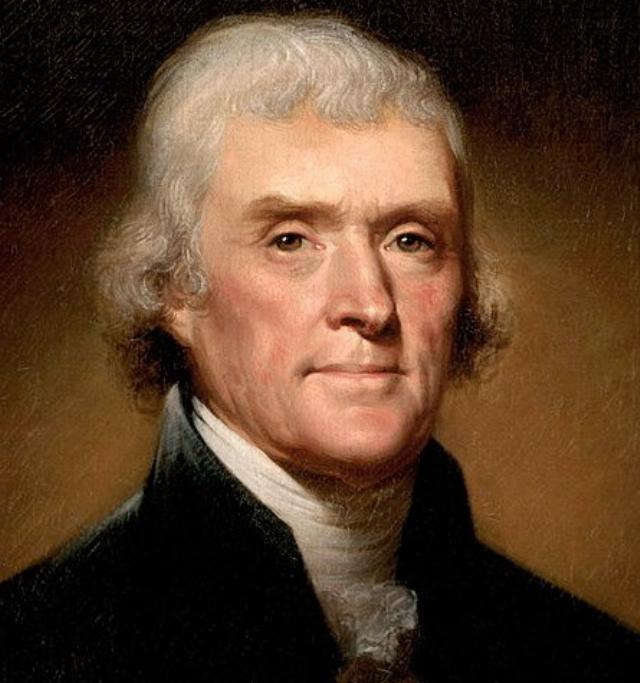

Image: Thomas Jefferson by Rembrandt Peale (cropped). Public domain.

When Jefferson, John Adams, and Ben Franklin confronted the crisis that could cripple the American economy, Franklin, the Quaker, argued that America’s trade in the Mediterranean was relatively insignificant, so American merchant vessels should avoid that sea.

Adams, a Boston lawyer familiar with maritime commerce, believed it would be a mistake to abandon the Mediterranean trade. Instead, he believed America should follow the European practice of paying “tribute” to the One True Faith—in practice, “protection” money. After all, if the mighty Europeans could not defeat these water-borne brigands, how could America, a nation without a navy?

Jefferson also knew it was common for the “Mussulmen” to take tribute for a certain period but suddenly accuse the Europeans of some violation, requiring fresh negotiations and a higher price.

In 1786, during a meeting between Jefferson, Adams, and Sidi Haji Abdul Rahman Adja, Tripoli’s ambassador to Britain, Adja demanded tribute equal to one-sixth of the new nation’s entire budget. When Jefferson asked why, because the infant U.S. had never attacked Tripoli, the Sheikh explained, “It’s the jihad.”

Jefferson learned that in Islam, the war between the religions is unending, with Believers required to oppress and dominate infidels who refuse to convert. The jihad requires imposing Islam on infidels and subjugating them for their stubborn refusal to adopt the “correct” religion. If the Americans wanted to sail on the Mediterranean, which belongs to Islam, they had to pay.

No wonder Jefferson wanted to fight. He was appalled by these “pirates” who had never entered what Tom Paine would eventually call “The Age of Reason” and waged a religious war. His plan, however, was relatively non-violent: Blockade the ports for years, if necessary. The “Mussulmen,” unable to put to sea, would forget sailors’ skills and be forced to learn agriculture, as the French had.

This would require a navy, although Jefferson, who would be remembered as the “Father of the Navy,” did not want an expensive “blue-water” navy with huge line-of-battleships. He imagined a modest, “white water” fleet with small, shallow draft coastal vessels to blockade Africa’s northern ports, preventing the cruisers from putting to sea.

In 1790, Jefferson, again in the U.S., became the first secretary of state under the new Constitution. His first presentation to Congress reported on the depressed state of commerce in the Mediterranean due to the menace of the Mohammadan cruisers. It included his long-standing recommendation that the U.S. build a navy to end this criminality perpetrated by a society still mired in a violent and benighted past.

In 1793, as his last project before retiring, Jefferson as secretary of state, Jefferson predicted a catastrophe on the high seas. Mere months later, “Algerine” pirates hijacked eleven more American merchant ships, enslaving another one hundred forty American passengers and crews.

When New Yorkers learned about the mass hijacking, the stock market crashed. As the news traveled along the Atlantic seaboard, every major port suffered canceled voyages, throwing sailors out of work and destroying merchants tied to shipping. What Muslims did to the American economy in 2001, their forebears mass hijacking did to the American economy in 1793.

In that same prescient, final report to Congress, Jefferson had again asked for a navy. On March 27, 1794, Congress finally decided he was right and to build six extra-large frigates. The U.S. Navy was thus born to deal with the kidnapping and enslaving of Americans in the Middle East.

In March 1801, Jefferson became president. His first military order was to dispatch a squadron of four warships to the Mediterranean because Tripoli’s pasha was threatening to attack American vessels.

By the time the squadron reached Tripoli in May, Pasha Yusuf had already declared war and dispatched a mob to overrun and loot the American Consulate, just as happened in 1979 in Tehran and Libya (modern-day Tripoli) in 2012. In those cultures, explicitly declaring war against an enemy people is insufficient. A mob must overrun, loot, and sack the offending country’s consulate.

Jefferson finally had a war he’d spent seventeen years contemplating. The war ended after four years of historic and legendary naval battles, celebrating such heroes as Stephen Decatur, Jr., after whom some twenty American towns and counties would be named. It ended with a dozen U.S. Marines leading an army of mercenaries in a land invasion “to the shores of Tripoli.”

President Donald Trump understood the role of military power in international affairs, especially in that Mediterranean quadrant of the planet. Whether dealing with ISIS (which he successfully did) or al-Qaeda, Hamas, Hizballah, and their patron, Iran, there is no possibility of civilized discourse and compromise because their jihad is eternal.

It’s striking that the patron saint of the original version of American Liberalism, Thomas Jefferson, understood this, too, and was not above calling Islam—in the most politically incorrect way—a religion of barbarians.

Sha’i ben-Tekoa’s PHANTOM NATION: Inventing the “Palestinians” as the Obstacle to Peace is available at Amazon.com in hard cover or a Kindle ebook. His podcasts can be heard on www.phantom-nation.com.

FOLLOW US ON

Recent Articles

- Trump and the Public Trust

- Trump’s First 100 Days: A Scorecard of Wins, Waits, and Wobbles

- Larry David: No Longer the Master of his Comedic Domain

- Mass deportations without ICE enforcement

- Harvard’s Tax-Exempt Status and Religion-Based Bequests

- The Net Neutrality Hydra: Twice Decapitated, Still Standing

- Cloward-Piven and the Migrant Invasion

- Acting on the Lessons of History

- Is Jamie Raskin Having a Psychotic Break?

- Mother or Monster?

Blog Posts

- The real goal of Trump’s tariff war

- IRS firepower: Actions speak louder than words

- A new ‘spur-of-the-moment’ leftist protest planned for May Day!

- Ugly details rolling out on just what the Milwaukee judge did hands hyperventilating Democrats another losing cause

- Maybe woke has been "berry berry bad" to me?

- How much due process is due illegals?

- No Tesla or victim love in Minneapolis

- This is what happens when you tell people the law doesn’t apply to them

- As predicted, AOC is clearly running for president

- The big surprise about that judge arrested for allegedly helping an illegal alien escape from ICE

- Multiculturalism’s Marxist roots

- Washington State’s racist policies and infanticide dreams

- The jig is up! Newsom busted for blowing state Medicaid dollars on homeless housing

- What a shame to see Elon Musk returning to the private sector

- The almost-terrorist attack you didn’t hear about