Democracy and the Donor Class

Among recent political events, perhaps the most notable has been the power of a small group of super-rich Americans to exercise outsized political influence. Recall how President Biden soldiered on despite sinking poll numbers, pleas from worried down-ballot Democrats to drop out, and the clear evidence of cognitive decline. Joe remained steadfast, but then overnight, he dropped out. Why? The dramatic decline in super-sized donations did the trick. When major contributors said, “No dough until Joe goes,” Biden surrendered to reality. If there ever was an instance of “money talks” in politics, this is it.

The donation upsurge following his exit was dramatic. The Kamala Harris campaign raised more than $81 million dollars during the 24-hour period following the President’s withdrawal. The Democratic National Committee and allied fundraising committees took in the largest sum of campaign donations in the entire history of U.S. election campaigning. Future Forward, the largest super-PAC in Democrat politics, received $150 million, a haul they attributed to donors holding back during Biden’s final days. Yes, many donations were relatively small from the 888,000 donors who gave during this period, but many were very large.

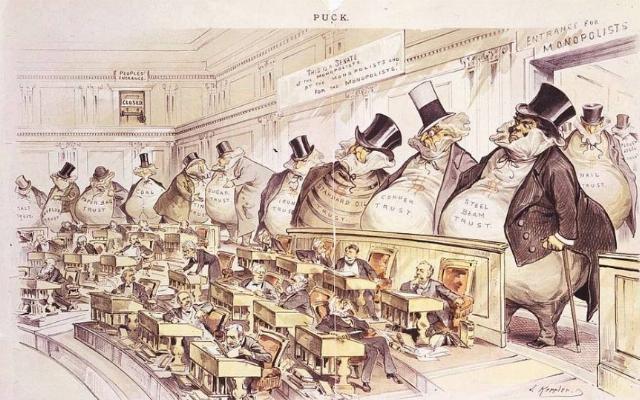

Big money has long infused American politics, but past references always connoted a bad smell to this money, so it was typically given secretly in cash-stuffed envelopes. Terms like “plutocrats” or “Robber Baron” are hardly neutral, and candidates often railed against “the Fat Cats” in favor of the “little guy.” No pro-business candidate would even openly admit that he sought funding from Standard Oil, though canceled checks would show otherwise.

The odious nature of “big money” has now been sanitized, so the super-rich bestowing millions are now innocuously labeled “the donor class,” a terminology suggesting high-minded charitable giving. Some of these numbers are staggering, For example, among the prominent Democrat donors are Netflix co-founder Rick Hastings (net worth $4.6 billion), who just gave the Harris campaign $7 million, while Timothy Mellon, heir to the Mellon banking fortune, donated $20 million to the Trump campaign, and such multi-million dollar contributions are hardly expectational.

The Founding Fathers understood how plutocracy threatened democracy. Many Founders were experienced campaigners, and, as was the custom of the day, one sought votes by throwing raucous parties with free food and liquor, so they obviously knew the connection between money and gaining votes. Great wealth was deemed a potential threat to the Republic -- you could buy an election.

The Founders knew that it was impossible to legally exclude the wealthy from politics, so they built into the Constitution itself multiple impediments to plutocracy. Central was awarding power to people whose livelihoods made them relatively immune to financial enticements, notably self-sufficient farmers (called yeomen farmers), tradesmen, and small merchants. For the Founders, these independent citizens were to be found in the state legislatures, especially the lower house, and thus were the bulwark against plutocracy. State legislatures -- not the people directly -- thus elected the President by choosing Electors, and until 1913 and the 17th Amendment, possessed the power to choose U.S. senators. That these state officials owned property or paid taxes only further ensured their independence from the plutocracy. In short, for the Founders, having voters able to resist the rich and act independently ensured democracy. Now, by contrast, anything that denies political access to society’s most dependent would be condemned as “anti-democratic,” though this dependency makes them the most susceptible to selling their votes.

The rise of the “donor class” as the political arbiters reflects a shift from the power of labor to the power of capital. That is, when campaigns were cheaper, power resided in those able to deliver large numbers of voters. “Bosses” such as Chicago’s Mayor Richard J. Daley (not personally wealthy) commanded an army of workers (many of whom were city employees) who guaranteed that nearly every Chicagoan voted for a Democrat. Precinct captains that failed to deliver Democrat majorities on Tuesday were unemployed on Wednesday. Labor unions such as United Auto Workers similarly helped mobilize voters on behalf of the Democrat party. Candidates were often chosen in smoke-filled backrooms by those whose very livelihood rested on satisfying the electorate. Today, the Democrat movers and shakers are more likely to throw an expensive fundraiser in a $20 million dollar Silicon Valley mansion prior to bestowing their blessings.

The rise of the “donor class” as the political arbiters reflects a shift from the power of labor to the power of capital. That is, when campaigns were cheaper, power resided in those able to deliver large numbers of voters. “Bosses” such as Chicago’s Mayor Richard J. Daley (not personally wealthy) commanded an army of workers (many of whom were city employees) who guaranteed that nearly every Chicagoan voted for a Democrat. Precinct captains that failed to deliver Democrat majorities on Tuesday were unemployed on Wednesday. Labor unions such as United Auto Workers similarly helped mobilize voters on behalf of the Democrat party. Candidates were often chosen in smoke-filled backrooms by those whose very livelihood rested on satisfying the electorate. Today, the Democrat movers and shakers are more likely to throw an expensive fundraiser in a $20 million dollar Silicon Valley mansion prior to bestowing their blessings.

This new class of political maestros -- hedge fund CEOs, tech entrepreneurs, venture capitalists, and the like -- lack any personal connection to voters. Voters angry at terrible schools do not visit Rich Hastings’ office to complain. Untrue in the Chicago of Mayor Richard J. Daley, where the local alderman, and perhaps the mayor himself, would hear all about it. To be sure, sizable donations were necessary under the old order and were solicited, but the ability to deliver something of value to actual voters got you elected.

Today, by contrast, it is the mega donation itself, not performing any service for the voters themselves, that becomes crucial, so a candidate unable to gain “donor class” support is history. Even a Mother Teresa-like candidate would now be required to hold a soiree with these Fat Cats, perhaps in Beverly Hills, if she contemplated running for office.

Soliciting millions is thus an “election” where a few hundred people vote with their checkbooks. In this “election,” Michael Bloomberg (net worth $104.9 billion), who donated $20 million to the Biden campaign, voted 20 million times; Joe Average, who mailed in $25 to the Biden campaign, voted a mere 25 times. It was entirely predictable that Kamala Harris quickly became the dominant Democrat candidate when the donor class anointed her. A paltry influx of funds would have doomed her.

Moreover, under today’s money-intensive rules, merely possessing a gigantic “war chest” will carry the day since rivals will be reluctant to compete against this well-financed competitor. An ability to raise prodigious sums becomes, in and of itself, a qualification for office apart from any connection to actual voters. In the early Republic, being a military hero -- Washington, Jackson, Taylor -- was the pathway to victory; now it is fundraising skill,

The Founders dreaded the power of money. It would be as if James Madison (1752-1836) were contemplating running for office but got wind that his wealthier neighbor had bought a hog farm, built a Bar-B-Que sauce factory, and a distillery to out-party the less affluent Madison. Madison could only hope that citizens could forego these lures and choose instead the man who would go on to establish the Bill of Rights.

Bad as the past gluttonous campaigns were, however, voters in Madison’s day could feast for free and thus receive something of value for their bought vote. But what did voters in 2020 get from the $5.7 billion spent during that presidential campaign? (The 2024 Presidential campaign is expected to cost $10,7 billion.) They got Biden, but in the bargain, they also got an often-unwelcome tsunami of print and media messages. The real beneficiaries, of course, were the thousands of consultants, internet influencers, event coordinators, TV actors, speechwriters, pollsters, and data analysts feasting on hyperexpensive campaigns.

The donor class is basically funding the campaign industry, particularly the mass media that soaks up most of the cash. Perhaps the $5.7 billion spent in 2020 would have been more appreciated if it had funded six months of all-you-can-eat-and-drink gluttony. Voters would then have gotten something of tangible value for their vote, and what could be more democratic?

Image: Joseph Keppler

FOLLOW US ON

Recent Articles

- Biden's National Censorship Regime

- Four Years, Five Fiascos: The Toll of Government Overreach

- The Legacy of the Roberts Court

- Parental Rights at Risk from Tyrannical State Overreach

- Alexander Hamilton: A Brilliant and Conflicted Leader

- The Death of the Center-Left in America

- ‘Make Peace, You Fools! What Else Can You Do?’

- When Nuclear Regulation Goes Awry

- The Danger of Nothing

- A New Pope With Courage

Blog Posts

- Pope Francis kicked an important can down the road

- Media hypocrisy: Hegseth must go because he’ll get us all killed

- Britain bans French philosopher who conceptualized the 'great replacement' theory, from entering country

- AOC versus visionary leadership

- The color revolution waged by our judiciary

- Fredi Otto, the new Greta Thunberg

- Why Democrats should become Republicans

- Terrorism works?

- Are we prepared for a new Chinese period of the warring states?

- Trump challenges the Fed

- The last Austrian standing

- Tim Walz: helping China colonize Minnesota?

- Another insubordinate officer?

- Keeping terrorists in America

- Celebrate Earth Day by not burning a Tesla