The Truth About Operation Wetback

Seventy years ago in 1954, immigration authorities created a mass deportation program in the face of out-of-control intrusions at our southern border. Then, like now, the gravity of the problem called for a dramatic policy response. Unlike now, the federal government rapidly responded, creating a system of roaming “deportation parties” concentrated on border-area factories and farms, netting tens of thousands of illegals in its first few days. The model, which would establish Border Patrol and ICE as we know them today, would later be dubbed, “Operation Wetback.”

Intensely reviled by the globalist Left even to this day, the program is recurringly attacked in mainstream outlets and scholarly journals as yet another blot on America’s trail-of-tears history. As something of an immigration scholar myself, one of the better examples of academic treatment I’ve come across is a 2006 paper from UCLA African-American Studies professor, Kelly Lytle Hernández. As she shows, Operation Wetback offers plenty of guidance on how to deal with the current border invasion, especially in reclaiming deportations and border control as essential to both receiving and source countries alike.

No doubt surprisingly to some, Prof. Hernández writes in the piece that “cross-border research [into the program] transforms the typically nation-bound and time-bound narrative of Operation Wetback into an unexpected story of evolving binational efforts at migration control” -- that is, “binational” efforts between the U.S. and Mexico such as “collaborative deportations, coordinated raids, and shared surveillance.” Few would know or at least admit that Operation Wetback was indeed a “binational effort” and essentially co-created by the Mexican government; such is the degree of disinformation and slanted revisionism of the program. As Hernández recounts in her piece, due to Mexican agribusiness facing upward wage pressure from what had grown into a mass outflow of domestic laborers by the mid-1940s, Mexican officials met with State and Justice department officials and successfully negotiated for things like an increase in U.S. Border Patrol officers on the border.

Capturing the sentiment on the other side of the border at the time, Hernández writes: “Mexican newspapers, politicians, and activists all tried to convince [would-be illegals] to stay in Mexico… remind[ing] them of their duty to participate in the economic development of Mexico by working south of the border.” So patriotic, nationally-minded, and focused on curbing the exodus, Mexican officials “attempted to directly interrupt illegal labor migration to the United States” (think of their simple refusal to deport U.S.-bound migrants today) while some in government even called for “turning intransigents among them into ‘forced labor’ within Mexico.” (Emphasis mine).

In response to this emigration crisis, “[o]fficials of the two countries rushed memos and agreements back and forth regarding how they could independently and collaboratively control the flow of undocumented Mexican immigration…” What eventuated was “officials in each country publicly announc[ing] that the US Border Patrol would soon launch Operation Wetback…” On-the-ground cooperation was manifested with officials like U.S. Chief Patrol Inspecter Fletcher Rawls and his Mexican counterpart Alberto “Hand of Steel” Moreno, who, Hernández says, showed the “expanded possibilities of policing and punishing unsanctioned migration when US and Mexican officers cooperated along the border.”

In response to this emigration crisis, “[o]fficials of the two countries rushed memos and agreements back and forth regarding how they could independently and collaboratively control the flow of undocumented Mexican immigration…” What eventuated was “officials in each country publicly announc[ing] that the US Border Patrol would soon launch Operation Wetback…” On-the-ground cooperation was manifested with officials like U.S. Chief Patrol Inspecter Fletcher Rawls and his Mexican counterpart Alberto “Hand of Steel” Moreno, who, Hernández says, showed the “expanded possibilities of policing and punishing unsanctioned migration when US and Mexican officers cooperated along the border.”

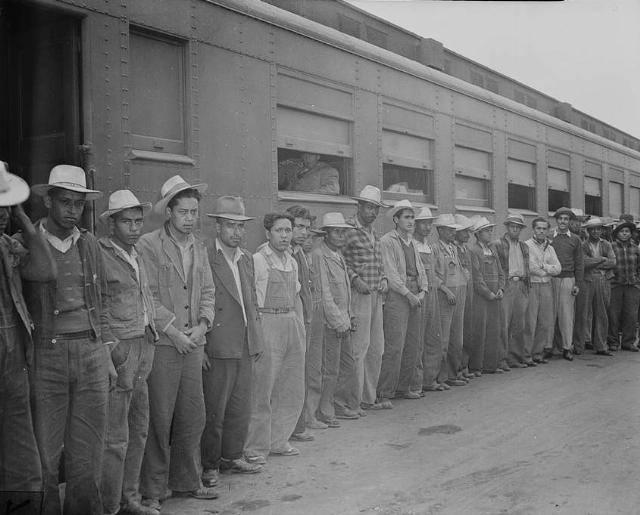

What did the program look like? One of the earliest deportation parties netted a group of illegals over 6,900 in number in McAllen, Texas -- deportations have been as low as 59,000 in the current administration. Apprehensions of deportable aliens quickly rose from 12,000 to 30,000. Later, over 50,000 aliens from central Mexico alone were airlifted home, marking the beginning of what we today call “ICE Air.”

As a result, illegals began to avoid intruding into Texas, choosing to go through California’s border instead. In response, immigration authorities delivered our first border wall: 4,500 feet of 10 feet-high chain link fencing (enough to force circumventers to enter dangerous desert lands and mountains). While locals on the Mexican side resisted, Mexican solders were actually deployed to patrol and protect the fence build-up. Mexican authorities even began deploying shaming tactics on their own deported illegals, for instance, by shaving their heads before releasing them back into Mexico.

Today, mass emigration is just as bad for Mexico (and the rest of Latin America) as it was then. Likely more so, in fact. How much would the obscenely fatalistic and kleptocratic narco-state reverse its chronic malaise if the tens of millions of Mexican people who have invaded our own country over the last several decades had actually been forced to stay put and stew in the sea of Mexico’s failed policies? In essence, unregulated migration acts like a safety valve that releases pressure off the (usually) corrupt elite of the failed nation in question. Open-borders do-gooders should know that encouraging illegal outflows, rather than hindering them, does much to keep these criminal elites in place.

Mexico, of course, has changed a lot since Operation Wetback, today demanding from us anything but solutions at our border. But, on top of threats of tariffs and border closures, reminding the public on both sides of the border when Mexico’s elite showed actual care and commitment for its national future, its government can be pushed to help reverse the armless invasion at our border, as it once did. In honor of such binational cooperative efforts like Operation Wetback, why not start a Fletcher-Moreno Day? Or, rename DHS’s headquarters the Fletcher-Moreno building? Such small efforts would, at least, create a constant reminder for top immigration staffers that cross-border illegal-alien flows demand cross-border cooperation and control.

Image: Library of Congress

FOLLOW US ON

Recent Articles

- Deep Dive: The Signal Chat Leak

- Mark Steyn’s Reversal of Fortune

- Where We Need Musk’s Chainsaw the Most

- Trump Is Not Destroying the Constitution, but Restoring It

- The Midwest Twilight Zone and the Death of Common Sense

- Hijacked Jurisdiction: How District Courts Are Blocking Immigration Enforcement

- Transgender Armageddon: The Zizian Murder Spree

- Jasmine Crockett, Queen of Ghettospeak

- The Racial Content of Advertising

- Why Liberal Judges Have a Lot to Answer For

Blog Posts

- Amid disaster, watch Bangkok clean up and rebuild

- Katherine Maher shoots herself, and NPR, in the foot

- A visit to DOGE

- You just might be a Democrat if ...

- Yahoo Finance writer says Trump’s tariffs will see America driving Cuban-style antique cars

- Kristi Noem and the prison cell

- Dividing the Democrats

- April 2nd: Liberation Day and Reconciliation Day don’t mix

- Red crayons and hospital gowns

- The Paris Climate Agreement was doomed from the start

- Well excuse me, I don't remember

- Bill Maher goes civil

- Mass shootings: we're all survivors!

- Tesla and a second

- Snow White: a bomb for the ages