Claiming Statehood

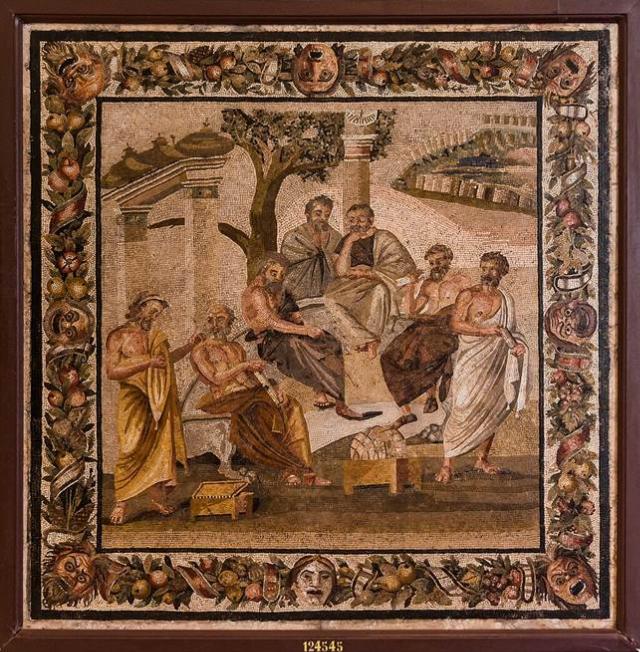

What does it take to make a good society? In the West, not only liberals, but even conservatives of the activist disposition, have tended to think that we have really succeeded in creating a just society, if not a “good society,” in the Platonic-idealist (and illiberal) sense. As outlined in his dialogue Republic, Socrates’s famous pupil originally envisioned an ascetic warrior society without the right to family and private property. We have gone about it in another way.

Arguably, the Western society, a product of innumerable, intertwined trade-offs, represents the pinnacle of social adaptation and civilized compliance. Resting on a foundation of Judeo-Christian ethics and ideas of the Enlightenment, we have built an orderly society with a tripartite separation of powers. Since the post-war years, we have also had “redistribution of wealth” to show for it — also known as “welfare.” At least, we are “on our way” to reaching the political-moral goals of our secularized culture… or so we are told by those pushing for ever greater degrees of economic equality (or “equity”), regardless of the personal contributions of the individual citizens to the community. “Progress,” as they say.

Convinced of our ideological victory (and the “end of history” as prematurely declared by Francis Fukuyama) after the collapse of the Soviet empire, we have tried — in the bidding way — to export our social order to the Muslim world, following military campaigns in Afghanistan and Iraq. (Neocon state-building proved an expensive adventure!) For several decades, we have also worked — in the alluring way — to sway African states from tyrannical forms of government towards our own by offering help to develop agriculture, fishing, and industry. We have put our faith in our Western value system, believing it to provide a universal cure for social misery and injustice.

The steady influx of migrants from the Third World has been taken as indisputable evidence of our superiority as social engineers. As soon as people in other parts of the world have a choice, they are willing to break up and defy all kinds of dangers to get here. No wonder that we have been in the habit of thinking that our way of life has won once and for all. Accordingly, we have been seduced by the narcissistic delusion that everybody else must have an irresistible urge to become like us.

However, there is a bit of a paradox calling for reflection in the relationship between the West and the rest. At the same time as we reckon Western standards of social order to be victorious in the world, we continue to criticize ourselves for past crimes against other peoples. And in belligerent manifestos, where the conspirators claim to be particularly perceptive of “hidden power structures” and are used to operating with conflated ideas of class and race conflicts as the driving forces of history, deliberately inciting one group against the other, Westerners are accused of still succumbing to “white privilege” etc. The Marxist-Leninists, orphaned and forced to work in the shadows since the ban on the Bolshevik mother party in 1991, have been waiting for their chance and found a new home for the maladapted “social-justice” warriors in the “struggle” for the Third World (in addition to the “struggle” for ethnic and sexual minorities).

In the absence of timely exposure and intellectual resistance, the subversive forces working single-mindedly on the downfall of the West have been allowed to organize and disrupt life in the cities and on the campuses. It has gotten to the point where Western civilization seems to be committing a protracted suicide while the rest of the world looks on with a mixture of amazement and glee.

Making up for the unpardonable sins of Western colonialism (i.e. as opposed to, say, Arab, Chinese, and Japanese colonialism), whose severity is nothing but increased by the (suspected) racist element, we — Western taxpayers — have invested outrageous sums in the development of Third-World countries. (In the Western countries, where it used to be the Christian mission that attracted the professional benefactors, an entire foreign-aid industry, the counterpart of our social industry, has been set up for the purpose of charitable distribution.)

We try our best to imagine that we are supporting a process towards democratic societies with independent courts and incorruptible law enforcement. What happens right before our eyes, however, is something completely different. On a continent, where tradition in most places divides power between tribes and dictates that the tribe put its own members above others, there is no real openness to Western ideas of “liberty, equality, and fraternity” as demanded by enlightened citizens during the French Revolution. Life goes on as usual, albeit with showcase changes on the surface to attract Western sponsors. (Those of us, who have dedicated our lives to spreading civilization to the darkest parts of the world and even make a living from it, simply love the little sunbeam stories that dazzle public opinion in the West, creating the illusion of real change.)

Of course, no exotic tyrant in his right mind, whether socialist or Muslim, refuses to accept money from masochistic Westerners trying to buy a better conscience. While they shower us with rehearsed complaints about past exploitation of their resources, the tyrants take our money without blinking an eye.

As of late, African tyrants, initiators of Marxist-collectivist experiments, depleting natural resources and killing private enterprise, have grown tired of listening to Western human rights defenders and feminists. The obsession with sexual minorities — a phenomenon likely to turn any morality upside down, as if it had been planted as a hybrid-warfare bomb by malicious strategists — we have all to ourselves in the West. However, unable to organize beyond village level the UN-recognized member states, which they run like slave plantations, the tyrants are — as always — in need of help from outside. Preoccupied with political survival (and existential survival after harassing opponents), they expectantly turn to new masters: Russians and Chinese. While the former deliver on the promise of military expertise, the latter undertake the development of infrastructure, e.g. asphalted roads and railways, in the African wilderness. In return, the tyrants, selling out their countrymen, give the new colonizers access to the riches of the underground.

As far as a free press, democratic institutions, and the rule of law are concerned, we pretty much stand alone in the West. Victims of our own (self-righteous) naivety, we have vastly underestimated the importance of religion, customs, and history for Third-World resistance to change, especially outside interference. So, after all, we have not really won the war of ideologies.

Disillusioned and disgraced after his failure as an adviser to the tyrannical ruler (Dionysius I) of Syracuse, Plato died in Athens. In the work of his old age, the dialogue Laws, which testifies to the empirical modification of his thinking, there is a noteworthy softening of his attitude to human needs and the organization of society. As something new, compared to the militarist-communist recommendations from Republic, he stresses the necessity of written laws, besides allowing families and private property rights.

Neither happiness nor peace awaits humanity in the utopian ideal society. The fantasy of total — or final — solutions invariably ends in suffering and death. Democracy, as invented by the Greeks, is the formula. In biological terms, we are not created equal: some are healthier, smarter, or more beautiful than others. However, it is in our power to insist on human freedom and dignity. We do not create each other, but what we can do together is to create institutions that secure the individual citizen’s (a) right of participation in social affairs, (b) equality before the law, and (c) protection against injustice from other citizens.

In order to resist the temptation to become dogmatically insistent in the totalitarian way when dealing with our fellow citizens, we must come to terms with the reality of an imperfect world inhabited by imperfect people. Quoting Thomas Sowell:

There are no solutions, there are only trade-offs; and you try to get the best trade-off you can get, that’s all you can hope for.

Image: Public domain.

FOLLOW US ON

Recent Articles

- Why Do Democrats Hate Women and Girls?

- There is No Politics Without an Enemy

- On the Importance of President Trump’s ‘Liberation Day’

- Let a Robot Do It

- I Am Woman

- Slaying the University Dragons

- Canada Embraces European Suicide

- A Multi-Point Attack on the National Debt

- Nearing the Final Battle Against the Deep State

- Now’s the Time to Buy a Nuke (Nuclear Power Plant, That Is)

Blog Posts

- Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney is accused of plagiarizing parts of his Oxford thesis

- France goes the Full Maduro, bans leading opposition frontrunner, Marine Le Pen, from running for the presidency

- Bob Lighthizer’s case for tariffs

- An eye for an eye, an order for order

- Peace on the Dnieper?

- Tesla protestor banner: 'Burn a Tesla, save democracy'

- Pro-abortionists amplify an aborton protest's impact

- A broken system waiting to crash

- The U.S. Navy on the border

- Rep. Jasmine Crockett opens her mouth again

- Buried lede: San Francisco has lost 60,000 tourism-related jobs

- I’ve recognized manipulation in the past, and I see it now on the Supreme Court

- The progressive movement has led the Democrat party into a political black hole

- A Colorado Democrat’s immoral cost-benefit analysis to justify taxpayer-funded abortion

- We must reclaim Islam from Islamism